Adults with Prader-Willi Syndrome Show Prematurely Aged Brains, Study Shows

Written by |

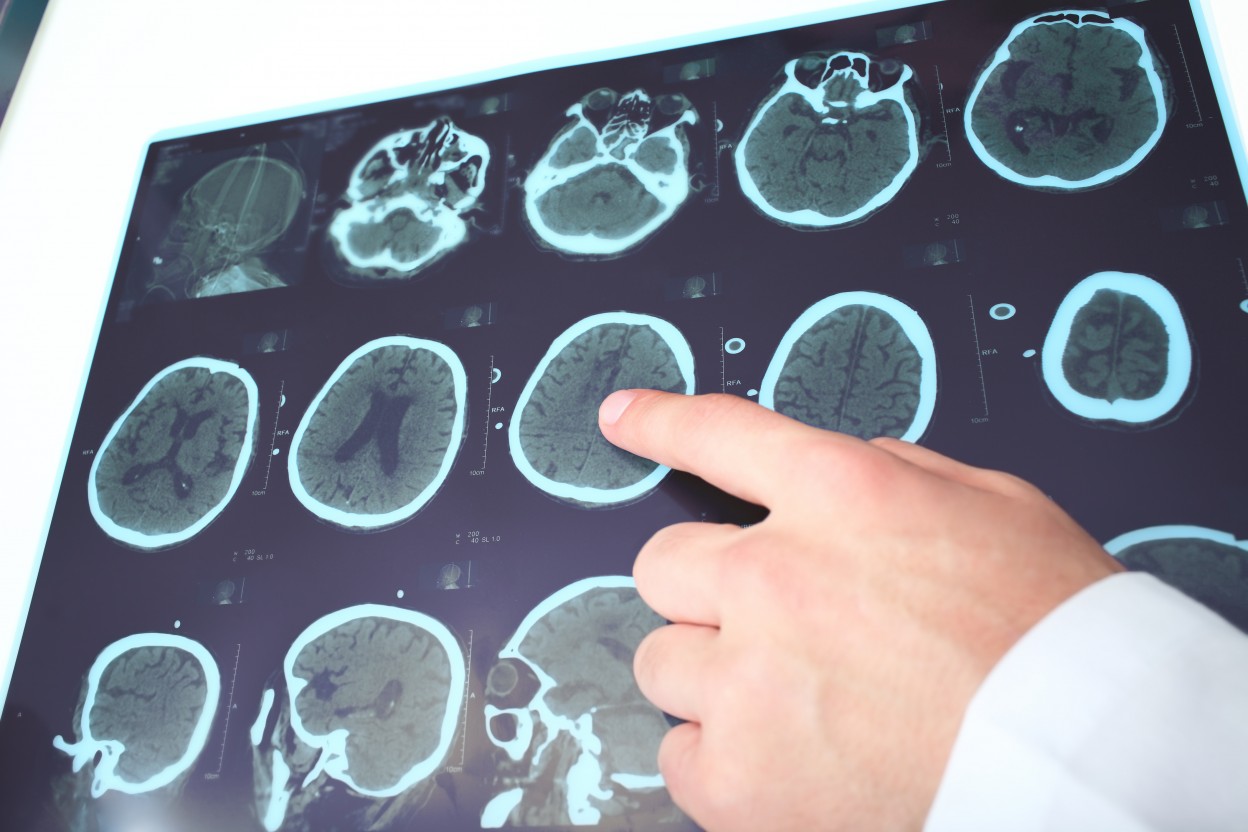

Adults with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) show prematurely aged brains, being on average 8.74 years older than their chronological age, according to a neuroimaging study. This was not associated with body mass index (BMI), use of hormonal or psychotropic medications, severity of repetitive or disruptive behaviors, or intelligence quotient (IQ).

The study, “Increased Brain Age in Adults with Prader-Willi syndrome,” was led by researchers at the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London in the U.K., and was published in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical.

PWS is the most common genetic obesity disease, and is associated with learning difficulties, and behavioral and psychiatric problems. Improved clinical management has extended the life expectancy of people with PWS, so investigating the neurological abnormalities of adult patients is an important step to understanding how these issues may impact their quality of life.

In the study, researchers relied on machine learning (an application of artificial intelligence that allows computers to learn and improve from experience) to teach a computer how to predict brain age based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 2,001 normal subjects, from 18 to 90 years old.

Then the team used the system to compare the predicted brain age of 20 adults with PWS (mean age of 22.6 years, and 70% male) with the predicted brain age of 40 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (mean age of 22.4 years, and 65% male).

Most of the PWS patients in the study (19 out of 20) had a paternal chromosome 15q11-13 deletion, the most common cause of PWS.

Results showed that, on average, the brain-predicted age difference of the PWS patients was 7.24 years older than in the matched controls.

Although the mean BMI of PWS patients was significantly greater than the controls (30.1 versus 24.1 kg/m2), this difference in body fat was not linked to the prematurely aged brains, given the fact that when PWS patients were matched with controls according to BMI, the older brain age of PWS patients was still observed.

The team also determined that the increase in brain age was not associated with the person’s IQ, use of hormonal and psychotropic medications, or severity of repetitive or disruptive behaviors (which are typical in PWS patients).

Researchers also compared the predicted brain age of one particular patient with PWS in the study — a 24.5-year-old man (BMI 36.9 kg/m2) who had PWS due to a rare genetic defect known as a SNORD116 microdeletion — with 95 healthy controls. They found that the brain age of the patient was about 12.87 years older than the controls.

PWS patients have an abnormal development in certain areas of the brain, and two competing hypotheses seek to explain the neurological and behavioral changes associated with the disease: premature aging and brain atrophy, or atypical and arrested development.

According to the team, “this neuroimaging study indicates that PWS is associated with an increased brain-age from early adulthood. This conclusion challenges the competing hypotheses (arrested development vs. premature aging) trying to explain structural brain abnormalities in PWS.”

The researchers stated “that there may be neurological implications of PWS in older age, which may have important clinical implications as the life expectancy of patients with PWS is prolonged.”

Further studies are nonetheless needed to better understand this increased brain age in PWS patients, and its relationship with obesity and other disease symptoms, they added.